Brass Olokun and digital Olokun. The Yoruba sea-god enters the metaverse. Are NFTs a new way of appropriating indigenous cultures or a bridge between traditional and digital art?

Appropriation is not appreciation!

Homo sum et humani nihil alienum a me puto (I am a human being and therefore nothing human is strange to me)

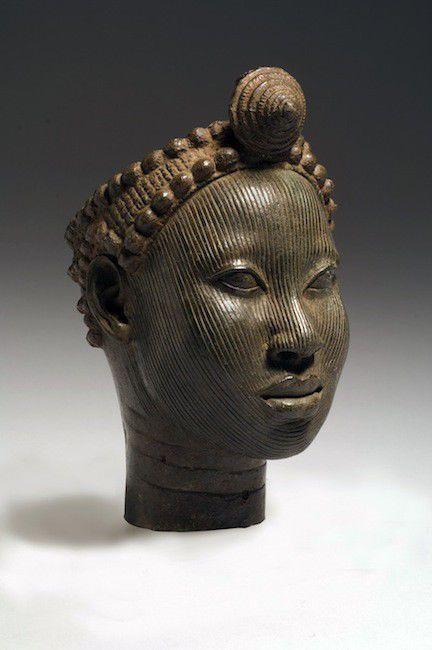

The ambition of the Heroji NFT collection is to resurrect ancient gods from around the world but some of these gods are still worshipped. Other NFT collections also celebrate indigenous cultures. One of our Herojis is Olokun, a sea god in Yoruba religion. There are only a few ancient representations. One of them is a brass head, a masterpiece which became a symbol of the appropriation of African culture by the Europeans but also of the resilience of the Yoruba people. It can seem exciting to transpose ancient figures in the digital world. But this raises an ethical question: are NFTs just a new way of appropriating indigenous cultures?

Reclaiming a masterpiece: the Olokun brass head of Ife

The meaning of art for the Yoruba people

Yorubaland spreads over a vast portion of West Africa. In medieval times (13th-15th centuries AD), kingdoms thrived and developed urban settlements such as Ife, Oyo, Owa in Nigeria. The sovereign led a refined life and commissioned artists to embellish his palace. But art had also a religious function. Creation of the world was conceived as an artistic endeavor. Like a sculptor, Obatala shaped the first humans out of clay. The urban settlements were also religious centers and artists had to supply the shrines with ceremonial masks, ritual objects and statues. So Yoruba art was both princely and religious, two aspects often combined since the power of the king was spiritual and worldly.

Ivory armlet worn by the king. White is the color of Obatala. It is decorated with human heads and animals and hunchbacks (it was believed they owed their difformity to Obatala.

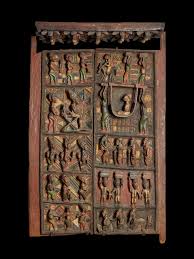

Carved wood panels of a palace door. On the left panel: the king and queen sitting on their thrones. On the right panel: a British official resting in a hammock.

This oshe Shango sceptre was used in ceremonial danses. Shango is the god of lightning and thunder. He consulted Orunmila, the gods of divination to know why none of his enterprises succeeded. The god prescribed sacrifices and offerings and told him to danse. Shango refused at first because he feared to lose his dignity. He ended up complying and his performances became widely popular and brought him a lot of money.

The brass heads of Ife

The Olokun head was the first to be found and its discovery and recovery by the Nigerian people is quite the epic tale.

In 1910, German ethnologist Leo Frobenius arrived in Ife, eager to acquire African artefacts. As said before, Ife was a political but also a spiritual center. According to the myth, the creation of earth by Obatala began at Ife, cradle of mankind. The brother of Obatala, Odudawa, founded a dynasty and his sons and daughters became rulers of kingdoms in Yorubaland. Frobenius heard stories of a marvelous statue of sea god Olokun who also had a special bond with Ife. It was believed that when Obatala created the world, the god emerged from the abyss of the oceans. Frobenius was taken to a palm grove nearby, shrine of Olokun and was shown a brass head.

He was awestruck : « before us stood a head of marvelous beauty, wonderfully cast, an antique bronze true to life, encrusted with a patina of glorious green ». And he goes on : « it was very finely chiseled, like the finest Roman examples ». Frobenius tried by all means to purchase the sculpture but was opposed by the Ancients and the British authorities who had at that time established protectorates in Nigeria. The head was kept by the priest, then by the king in his palace and was finally exhibited in the Ife national museum. Rumors had it that Frobenius was tricked and shown a copy but recent studies seem to confirm its authenticity. Frobenius didn’t return to Germany empty-handed. He brought back thousands of objects which he sold to German museums. The head of Olokun became an emblema of Nigerian identity and in 1973 it was chosen as symbol for the All-African games in Lagos.

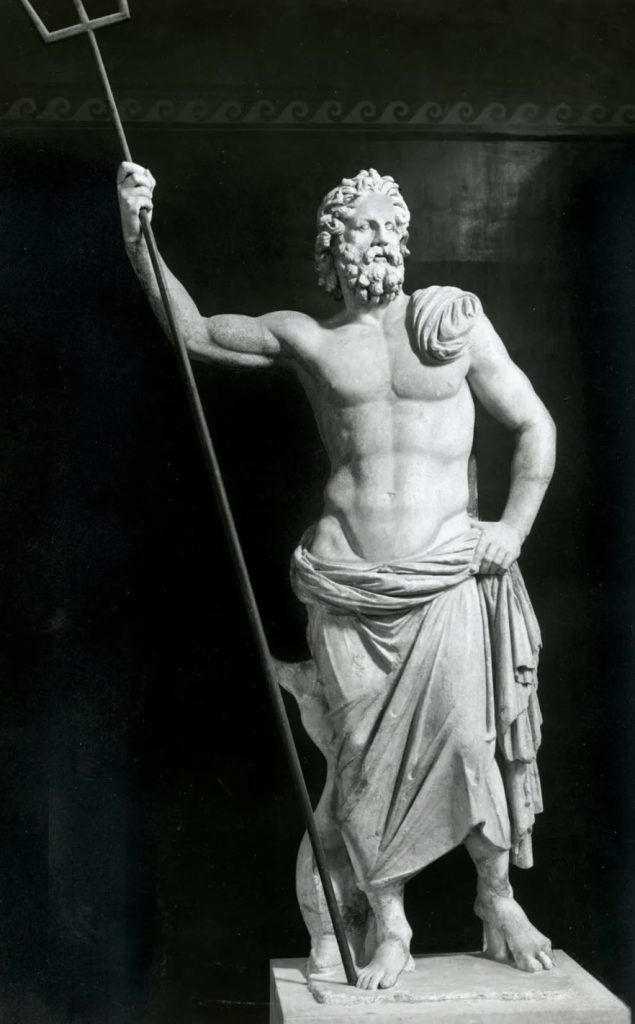

The Nigerians had succeeded in keeping the masterpiece in their homeland but another battle had to be fought. Frobenius was a complex character. He had a real interest for African art and made it popular in Europe at the beginning of the twentieth century but he remained a prejudiced white man with offensive and patronizing conceptions towards African art. He could not believe that the brass head which he compared to Roman examples was created by African artists. It was too perfect to be of African origin. He claimed that the head was cast by Greeks established in Ife in the 13 th century, descendants of survivors of the lost Atlantis. Olokun was in fact Greek god Poseidon. These wild misconceptions would influence the representations of Olokun often pictured holding a trident like Poseidon.

However the discovery in 1938 of several similar heads would confirm that not only were they African but that they were created by one workshop and perhaps even one individual artist. The copper alloy heads 35 cm high, dating from the 14 th century were made with the lost wax technique.

Why are only heads featured? Art is deeply rooted in Yoruba cosmology. Ori is a word meaning head. It is the soul, the spiritual guide and the destiny of each individual. Before being born, a human had to choose his ori, his good or bad destiny throughout life. The realism of the sculptures is very unusual in African art. It is now believed they are idealized but individualized portraits not of gods but of sovereigns. This is probably also true for the Olokun head. The intricate scarification patterns are also a means of individualizing the portraits. They show the person has reached manhood and is fit to be a warrior. They also turn the body into a work of art. Some of the sculptures are adorned with elaborate headdresses, a symbol of royal and divine authority. Olokun’s crown is formed by a decorated base topped by a crest with a rosette and a slightly bent plumette.

Most pieces ended up in the national museum of Ife. The discovery of these sculptures was the spur for the government to control the export of antiques.

Cultural exchanges between Africa and Europe

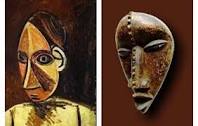

We shall not dwell on the enormous impact the discovery of African art had on European art in the beginning of the twentieth century.

But African cultures were also influenced by Europe. We have already mentioned how Olokun became identified with Greek god Poseidon. Olokun was the god of reflecting waters and Africans used the reflections on water to predict the future and communicate with the world of spirits. European mirrors became very popular and were used for divination and initiation rites. Little mirrors were placed in Olokun’s shrines. These mirrors like other European imports had a cost : twenty slaves for a mirror, 50 for an umbrella, 100 for a gun. According to the myth, Olokun challenged supreme god Olorun in a weaving contest. This reminds us of the Greek myth of Arachne, a maiden who boasted she was better at weaving than Athena. The angry goddess changed her into a spider. But perhaps there is no direct influence. Myths have universal elements and the challenge between a god and a mortal or between two gods is frequent in mythologies around the world. However in one version of the story, Olokun adorns herself with her finest clothes and admires herself in a mirror. This is obviously a borrowing from the story of Snow White and once again mirrors were imports that in Africa were sacred objects not instruments of narcissistic vanity.

Africans were obliged to convert to Christianism and of course that had an impact on their art. So cultural exchanges were asymmetrical and none better than Aime Césaire, a Martinican poet and politician has denounced the violence of colonization in his Discours sur le colonialisme: «Moi, je parle de sociétés vidées d’elles-mêmes, de cultures piétinées, d’institutions minées, de terres confisquées, de religions assassinées, de magnificences artistiques anéanties.”

“I speak of societies emptied of themselves, of cultures trampled, of institutions undermined, of lands confiscated, of religions murdered, of artistic magnificence destroyed».

We are no longer talking about appropriation of one culture by another but of negation and eradication. However things get complicated when we consider that Aime Césaire received a French education, wrote his speech in French and that his poetry is deeply influenced by Rimbaud, Baudelaire and the surrealists.

Roger Bastide sees the hybridization of African and Christian religions as a ruse : « syncretism is simply a mask put over the black gods for the white man’s benefit ». But one could argue that Yoruba culture persisted in hard times. It changed but that change was a way of adapting to the circumstances and surviving. We could also see this vitality during the slave trade which created a Yoruba diaspora in the New World. Yoruba people were torn from their homeland, submitted to Christianism, deprived of their family ties , mixed with other ethnic groups and yet they managed to keep part of their traditions. The Afro-brazilian candomble or the Cuban Santeria are syncretic religions that adopted catholic symbols and beliefs but are still deeply rooted in Yoruba culture. We could lament a loss of identity and a betrayal of the true values of the Yoruba people. But some specialists have pointed out that the Yoruba religion has never been rigidly orthodox. The Yoruba people are divided in many subgroups, each speaking their dialect. Myths and rituals vary from one area to another. By the way that is why Olokun is sometimes female and sometimes male. This versatility and plurality could well be the key to their resilience. They found the means to adapt in a new environment, to survive and even to thrive.

Indigenous cultures enter the metaverse. Olokun goes digital, reenchanting the world.

or Max Weber, the «disenchantment» of the Western civilization is the decline of magical and religious beliefs due to the progress of science. Mircea Eliade shows that myths can be emptied of their sacredness and when this happens they become «nothing more than literary tales devoid of real meaning». Nonetheless humans need stories as much as they need air, food, drink and love. Stories can reenchant the world that has lost its magic. Myths of different countries never cease to fascinate. The movie industry has since its beginning reappropriated myths. The worlds they create are fake, tinsel, with anachronisms and historical misconceptions but they fulfill a real need. We turn to mythologies past and present that have kept their magic bond with nature. Trends appear: Greek myths ruled the day with films such as Jason and the Argonauts, then came the Celts with the knights of the round table and nowadays Vikings and Norse are extremely popular.

Mythology has recently entered the digital world with video games and AI generated pictures.

We all know of Nft collections based upon animals (bored apes, kitties, flash zebras) but mythology and indigenous cultures are also entering the metaverse.

The legitimacy of these new projects

Many of these projects seek some kind of legitimacy by stating that they are preserving traditional and indigenous cultures and promising to give money back to charities and associations. We shall examine two very different projects based upon native Australian cultures.

The first one is the indigenft. The project is ambitious : «Indigenft is an authentic art project. Sale of NFTs will support and promote indigenous cultures». It also aims to unify «indigenous communities». Five Australian animals (kangaroo, koala…) have been chosen and avatars created by varying the backgrounds, the clothing and the accessories. The productions are cartoon style and closer to cryptokitties and bored apes than to the representations of these animals in traditional Aboriginal art. They have modern clothes and accessories : hats, ties, rappers jewelry, more surprisingly Viking helmets and gold crowns. The animals are funny but don’t really seem to illustrate indigenous art.

Traditional representation of a kangaroo

Artist Robert Young seems to have a more serious point of view on the subject which he has expressed in a recent article «indigenous art launches into the NFT metaverse». He wishes to encourage Australian artists to go digital for the following reasons :

- Artists can explore traditional themes with exciting new media.

- Nfts can give visibility and publicity to artists and promote communication among remote communities

- Financial benefits : there is a long tradition of indigenous artists having their work usurped by brands, media, private shareholders. Blockchain technology is valuable in addressing issues concerning authenticity and ownership.

He adds that Culture Vault is a new platform that «unlike other NFT platforms which often prioritize the quick buck reminds buyers and brands that NFT are not just about sales transactions. They are a prompt for storytelling, cultural enrichment and community engagement». And let’s listen to the lyrical comments of his daughter Lyn-Al: «for me the NFT space is quite similar to the spiritual world we call Dreamtime. It’s intangible but all powerful… I am excited for what the future holds».

And what about the Heroji project?

12 gods, male and female, from around the world have been selected after lengthy discussions. We focused on polytheistic religions because polytheism implies mythology and storytelling. At first it was decided to only select « dead » religions but that meant eliminating a lot of civilizations. Choices had to be made. There could only be 12 gods in order not to overburden artist Anais Zhang. There are no Polynesian gods since we had already chosen Australian Yawkyawk. One could object that they are part of two very different religious systems. We had to reject Navajo Estsanatlehi, Inuit Sedna, Assyrian Ninurta, Gugurang of the Philippines.

Some will be offended that we used their gods for our project, others will be sad that they have been overlooked.

The Heroji project does not celebrate any form of neopaganism, we do not embark our buyers on some new age mystical trek. The gods are mainly symbols of natural elements (wind, sun, earth, ocean etc) and their mission is to help promote ecological projects. Much research was done for each god and its culture. Some of that work can be seen in our website blog (articles present the gods but also delve into symbolism and myths). On our discord account, the section «XII heroes» showers our viewers with pictures of objects (sacred and of everyday use), garments, jewelry, architecture, landscape, fauna and flora. Few words: the pictures speak for themselves. Anthropologist Philippe Descola claims that to be human is to be different. In our global economy, the world has become standardized and uniform with mass produced goods. As soon as you open up to other cultures, you are rewarded with worlds of exuberant beauty and vibrant diversity and that fills the soul with joy!

And to end this article, a few words on Anaïs Zhang’s representation of Olokun. Our studies and her own research help her create the Herojis. They are original pictures. Only the head of Olokun is featured. This is not a reference to the ori, the soul in Yoruba cosmology. The artist adheres to the rules set for all the Herojis: only heads appear in the first phase or «drop» and we shall see the gods from head to toe in the next phase. The androgynous figure has African features but the complexion is not realistic. According to the rules, each god has five complexions that are symbolic: basic, warm, mellow, cold, vibrant. Anais Zhang wanted to highlight the god’s divine nature and his bond to the ocean, hence the choice of colors and the fish. Each Heroji has different headdresses. For some, the artist has imagined extraordinary sea-themed constructions. One of them is however a borrowing from the brass heads of Ife, a way of honoring the representations of Olokun in Yoruba art. The ritual scarifications of the sculptures have disappeared but the resources of digital painting with repeated motives and patterns are a striking equivalent. The emblemas that surround the god are accurate and help us identify Olokun: the blue tureens in which he is said to hide all his secrets, the mirror, Agemo the chameleon who played a crucial part in the weaving contest with Olorun.

The viewers shall decide if these representations of an African deity by a Chinese artist married to a Frenchman are legitimate.

Some of the Herojis are gods that are still worshipped. It was important to show that the team is aware of the issues raised by appropriation. But it is an exciting challenge to bridge the gap between ancient cultures and modern crypto technology. Just as some of the green projects shall try to unite indigenous knowledge and western science.

This article is part of a series that shows the «making of» our Herojis by comparing an ancient work of art with our nft. The brass sculpture is beautiful by its materiality. It is also very fragile. Digital pictures are immaterial and they can’t perish. Time cannot hurt them but they can be popular and then fall into oblivion because the public is fickle. Like the ebb and flow of ocean, Olokun gives wealth but can take it back when we have not served her right.

References

https://journals.openedition.org

https://www.nationalgeographic.fr

J. Verdun, May 2024